Henry Allison was born on the 27 Jan 1872 in Cullercoats, Northumberland, England to William Allison and Elizabeth Hornsby. That year saw the construction of the Albert Memorial in London, the first FA Cup Final between Wanderers F.C. and Royal Engineers A.F.C., and the Mary Celeste set sail from New York on November 7. It would be found on Dec 4, adrift in the Atlantic, deserted. 1872 also saw Thomas François Burgers become the State President of the South African Republic. He would hold this position until the British annexation in 1877. As is often the case, state decisions on global matters would have long reaching consequences for the people in my family.

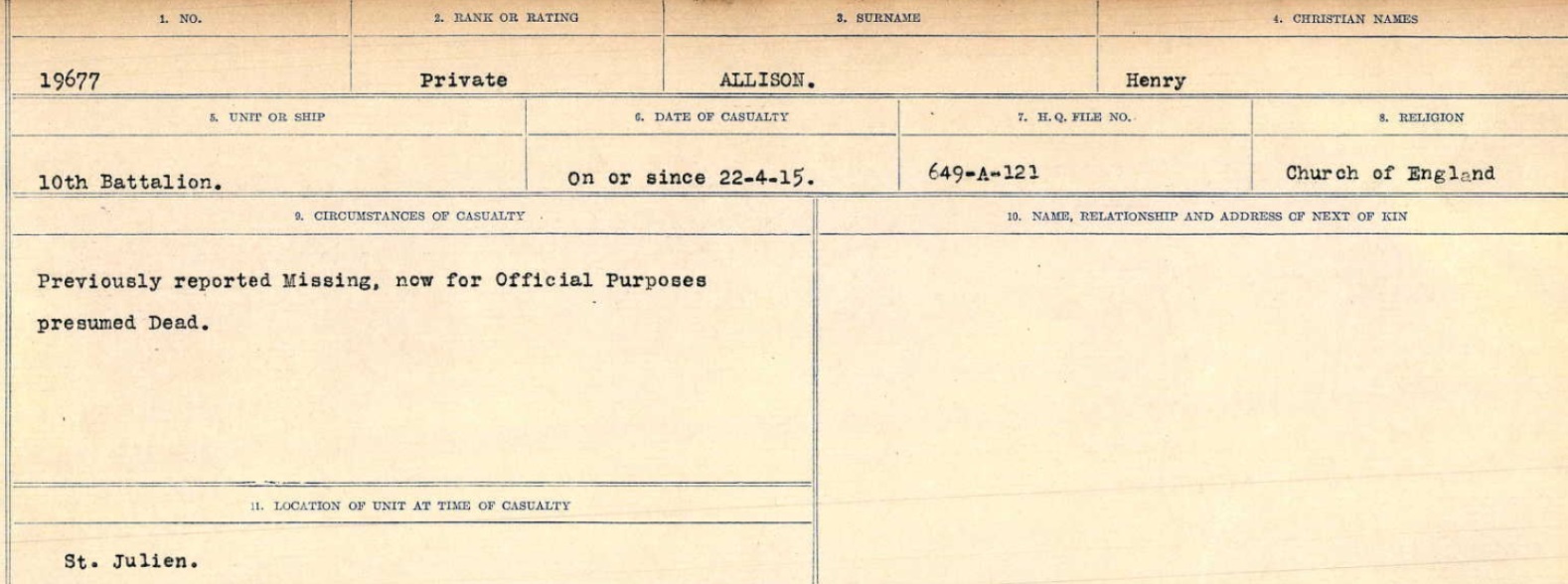

Henry Allison was the fourth of six children. His father dabbled in a number of jobs including linen draper, grocer, and an agent for the Tynemouth Gas Corp. Henry attended some sort of schooling as a young boy and by 1891, when he was eighteen years old, he was apprenticed to an ironmonger. In 1897, however, Henry left his family and home behind and moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada intending to farm. On Nov 29, 1899 he married Adeline Giles and just over a month later, on Jan 2, 1900, he signed up to serve with the Canadian Special Service Forces in South Africa. Discharged a year later, he returned to Adeline and Winnipeg where he fathered four children, Clifford, William, Dorothy and Eveline. He worked as a salesman and then a shipper until 1914 when Britain declared war on Germany on August 4. By September 4, Henry enlisted and made his way to Valcartier Camp in Quebec. He joined the 10th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, sailed for the UK with the first of the Canadians in late 1914, trained on the Salisbury Plains, and was sent to the trenches of France by early the next year. On April 22, 1915 he was reported missing, presumed dead.

Until I began doing ancestry research in 2008 my knowledge of the Allison branch of my family tree was limited to one name: William Allison, also known as Bill. Bill was my Nana’s father, but from what I understood the only thing he ever gave her was his last name. Despite this gaping hole in my original family tree, finding Bill’s family was surprisingly straightforward. It didn’t take me long to find his birth date and place and work backwards from there to his father, Henry Allison.

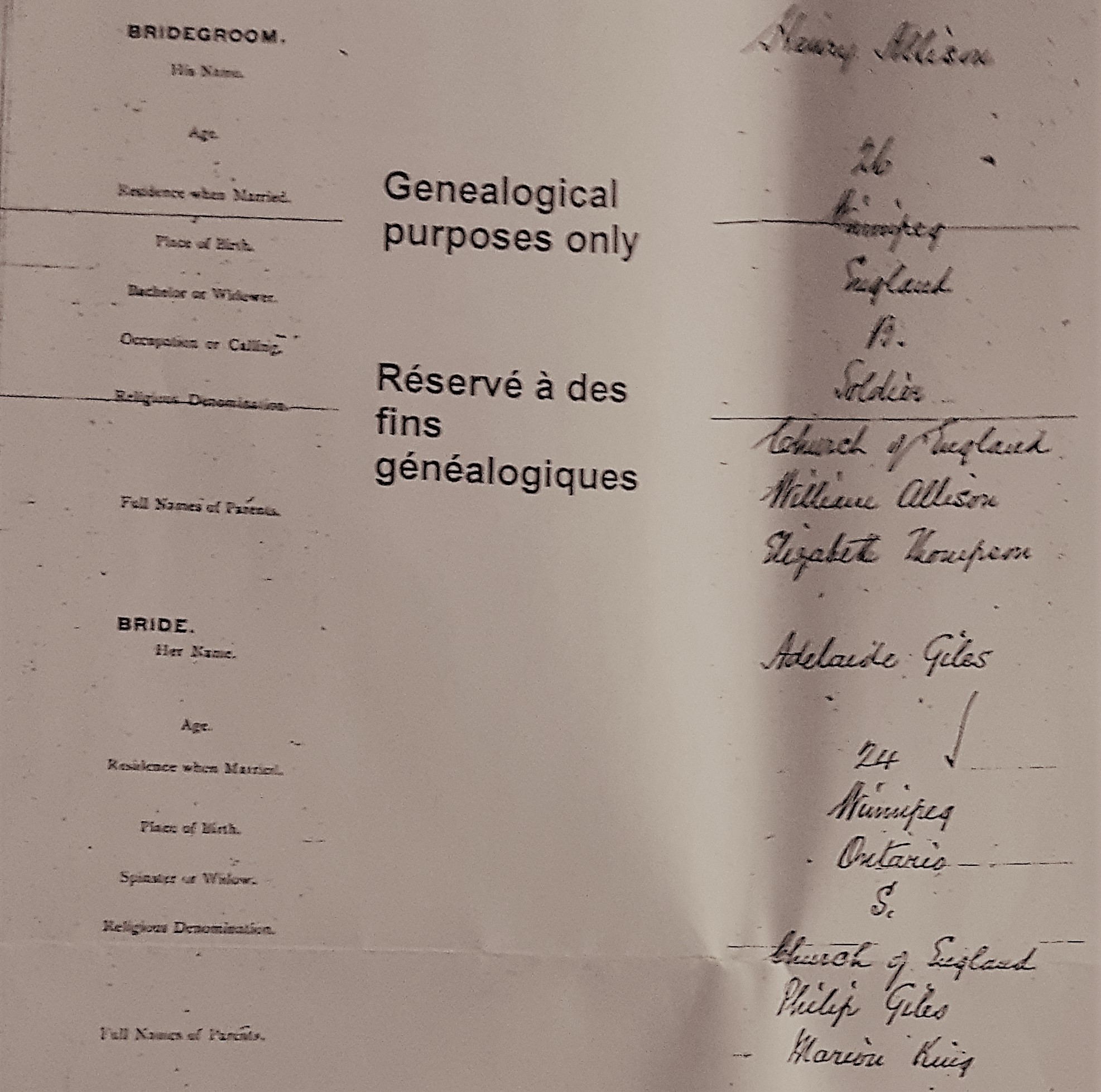

The 1911 Canada Census was my first view of Henry, his wife Addie, and three of his children. At that time they were living at 490 Magnus Ave in Winnipeg, with Henry working as a salesman. It also gave me a way to trace him back farther: a date and place of birth: January 1872 in England. With this census under my belt it was easy to jump back ten years to the 1901 Canada Census which supplied an exact date of birth, January 27, 1872. And his marriage record, which I found soon after, gave me his parent’s names, William and Elizabeth (née Thompson according to the certificate), though I realized I needed to take the information on this record with a grain of salt as it records his wife’s name as Adelaide Giles, when every other record says her name was Adeline.

I was able to find Henry’s parents in the 1891 England Census along with Henry, two older brothers, William and Watson; an older sister, Elizabeth; and three younger sisters, Margaret, Annie, and Mary. I haven’t been able to find Henry’s birth certificate yet, but I do have some of his siblings’, which list his mother’s last name as Hornsby. I can only blame the discrepancy between his mother’s last name on Henry’s marriage record on either Henry’s faulty memory or poor writing. The record that I have was written out in a fair hand, but I have a feeling it was copied from a less legible script. As I mentioned, his wife was noted as Adelaide not Adeline, so his mother’s maiden name Hornsby could have become Thompson through poor transcription.

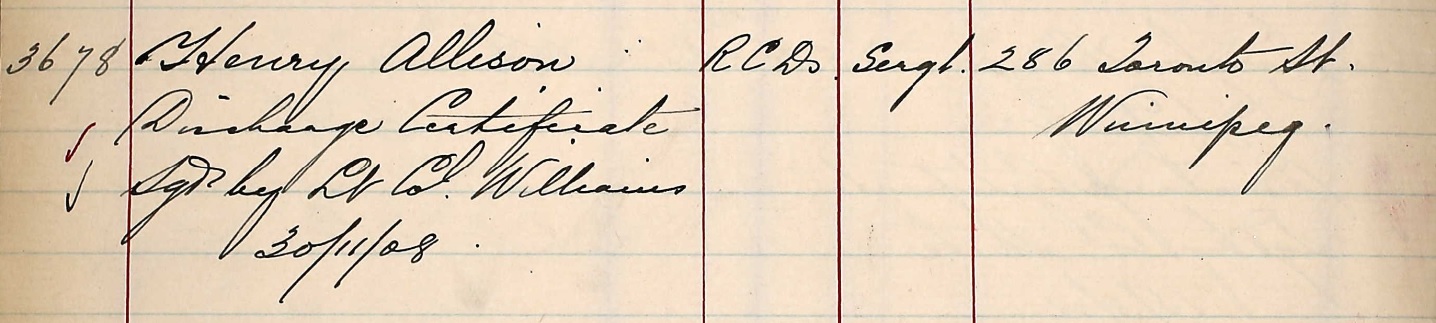

The 1901 Canada Census and Henry’s marriage record gave me one other interesting fact. Henry was a Sergeant in the R.C.D., the Royal Canadian Dragoons.

In 1872 Thomas François Burgers became the State President of the South African Republic, referred to as the Transvaal by the British. Five years later, when Henry was only himself five, Britain announced that it was annexing the South African Republic, though it was not until December 16, 1880 that the first Boer War broke out with a skirmish at Potchefstroom. After a number of victories for the Boers a truce was reached by August of 1881 and the full internal independence of the South African Republic was confirmed in 1884.

However, in 1886, gold was discovered in the South African Republic and Britain pushed for control once more. It would take over another decade, but in 1899, after the South African Republic had issued an ultimatum to Britain requiring them to agree to arbitration in their disputes and remove British troops from the border – an ultimatum that Britain refused – war broke out once more.

Henry, meanwhile, had grown to a young man. By the time he was nineteen he seemed set to follow in his older brother, William’s, footsteps as an ironmonger. But something happened and in 1897 he left England and his family behind for Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. In his immigration records he states his intention to become a farmer, but as far as I can tell he never did so. In 1899, Britain declared war on the South African Republic and their ally the Orange Free State, and Henry signed up to be a soldier.

Canada was in an interesting position. The young country did not have its own professional army and was split in its support for the war between French and English Canada. In the end, Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier authorized one thousand volunteers to fight in the British Army. In a sentiment that would be echoed in 1914, these original thousand believed they would be home by Christmas, but the Boers proved a tougher enemy than they had anticipated and soon another six thousand volunteers were sent over from Canada. Henry was one of them. Leaving his bride of only one month behind, Henry joined the Royal Canadian Dragoons on January 2, 1900 and departed from Halifax on the 27th, arriving in Cape Town on Feb 17th.

Fighting in the ‘B’ Squadron of the 2nd Contingent, Henry saw action at Johannesburg, Diamond Hill, Belfast, Cape Colony and the Orange Free State, and likely took part in the Battle at Leliefontein. After serving the one year he had signed up for, Henry was discharged and arrived back in Halifax on January 8, 1891. The war would continue until May 31, 1902 when the South African Republic surrendered to the British.

Almost nine months to the day of his return, Henry and Adeline had their first child, Henry Clifford, known as Cliff, with William Frederick and Dorothy May following in 1906 and 1909 respectively. In 1908 the Volunteer Bounty Act ensured that all veterans of the South African War received 320 acres of land or $160. Most chose the latter and since I have no record of Henry and his family moving out of Winnipeg in order to set up a farm, I assume Henry chose the money as well.

As I mentioned earlier, the family were still living in Winnipeg in 1911, at 490 Magnus Ave, and Henry worked as a salesman. In February 1914, his fourth child, Eveline Grace, was born. All of this paints the picture of a man doing well enough; able to support a growing family. Winnipeg was in a boom time at the start of the 20th century, becoming the fourth largest city for manufacturing by 1911 and the third largest city in Canada by 1914. All that was about to change, though, as war cast its shadow across the world.

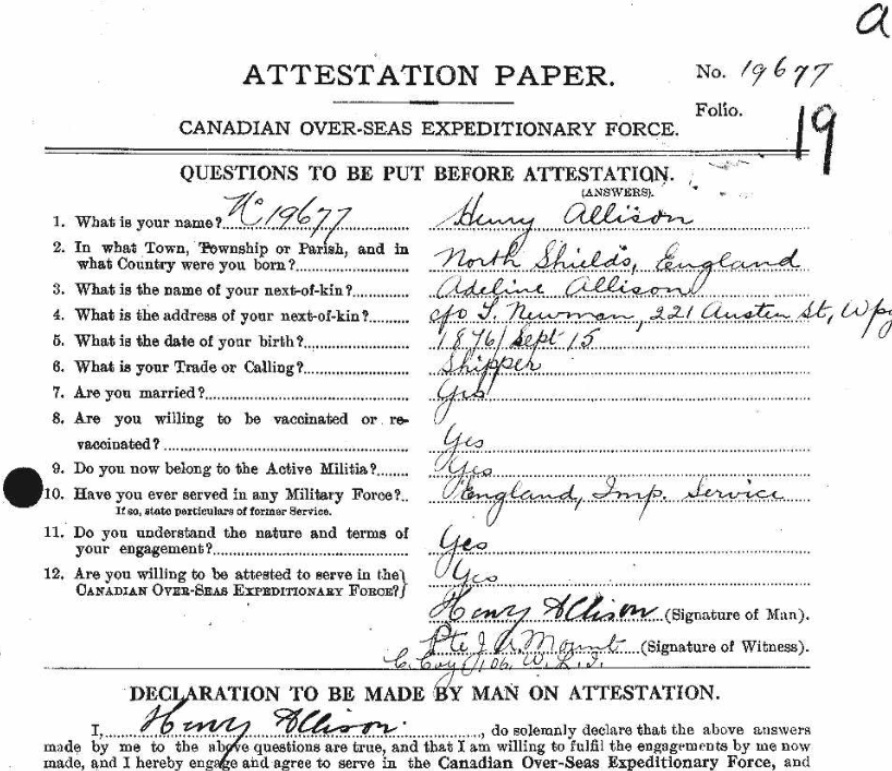

Four months after Henry’s youngest daughter was born the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated and less than two months after that Britain declared war on Germany. Canada authorized the creation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) by August 6, 1914. Soldiers were to be at least 5 foot 3 inches tall with a chest measurement of 33.5 inches. Medical examinations were stringent at first. Injuries, ill-health, flat feet and poor eyesight were all reasons for a man to be denied into the CEF. Soldiers were accepted between the age of 18 – 45, with the average age over the course of the war being 26. Henry, by 1914, was forty-two years old. He must have thought there was a chance he would be turned away, for in his Attestation Papers he lies about his birth-date. He says he was born September 15, 1876, which meant that when he arrived at the recruiting office in Winnipeg for his medical exam on the 4th of September they thought he was only 37.

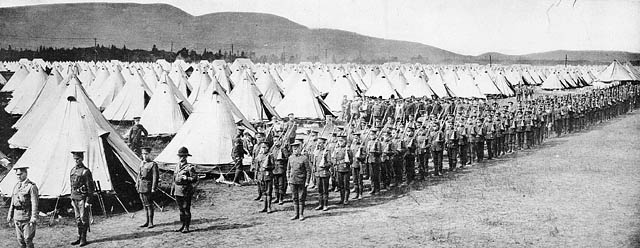

Lying about one’s age was not uncommon during the First World War. Patriotism and a sense of adventure meant men young and old were clamoring to join the CEF and they would lie and bribe their way in by whatever means necessary. For Henry, at least, it worked and he was recruited into the CEF and sent to Valcartier Camp, Quebec by Sept 26, 1914, joining the 10th Battalion, known colloquially as The Fighting Tenth.

Within a few weeks the Tenth shipped out. They arrived eleven days later in Plymouth and headed to a training camp at Salisbury Plain. In The Story of the 10th Battalion written by J. A. Holland for the Canadian War Records Office, Holland notes that the men trained “under weather conditions that were truly appalling, and during which hundreds of men suffered from the dreaded spotted fever, and pneumonia… Few, however, can realise to what extent the endurance and fortitude of the men were tried by the every day conditions of camp life”.

On February 4, 1917, exactly 65 years before I was born, King George V and Lord Kitchener did the final “Royal Review” of the battalions of the first Canadian Division. According to Holland, “The moment was epoch making. The men from far-off Canada, like Crusaders of old, were about to fare forth in defence of human liberty, and to pledge again in blood their loyalty to King and Empire”. Hindsight being what it is, I can’t really imagine how the men of the Tenth must have felt. All I can feel is an incredible sadness knowing what they would face over the next three and half years of war.

The Tenth left England on the 10th of February and disembarked in France in the Bay of Biscay on the 15th where they were taken by train to the town of Hazebruck in Flanders and then marched to Romarin by the 20th where they received instruction on trench warfare. By the end of February they were sent to the small village of Fleur Bais and for just over three weeks they endured standard trench duties. On March 25th, they were moved to a more active part of the front where they trained at Estaires until April 14th when they were taken by bus to Vlamertinghe and from there on foot to Wieltje and the trenches at Ypres. According to Holland, the men of the Tenth were told by the French garrison they were relieving that it was a very quiet sector they were taking on.

On April 22 officers of the Tenth were riding along the Elverdinge Road “when they saw rolling towards the British lines, behind the smoke of bursting shells, a dense cloud of yellowish-green vapour. It advanced slowly on the wings of the sluggish wind, crawling along the ground in heavy billows, unhurried and portentous”. It was the first use of mustard gas in the war and heralded the beginning of the 2nd Battle of Ypres.

I don’t know exactly what happened to Henry. I never will. In the CEF Burial Register, First World War, 1914-1919, his last known location was noted as St. Julien. Holland’s history of the Tenth gives details of the movements of the battalion the night of the 22nd if you are interested in following the decisions made, but suffice it to say that at 11:45pm the Tenth was given the order to advance on the German position at St. Julien Wood. Fifty yards from the woods the battalion had to smash through an unexpected hedge and the noise they made alerted the Germans to their presence. Rifles and machines guns were turned on the battalion. Lieutenant-Colonel Boyle, the Tenth’s commanding officer, fell in the fight. His second in command, Major MacLaren was hit and then killed by a shell on route to hospital. Of the 816 men who took part in the advance on St. Julien Wood only 193 survived. Henry’s body was never found.

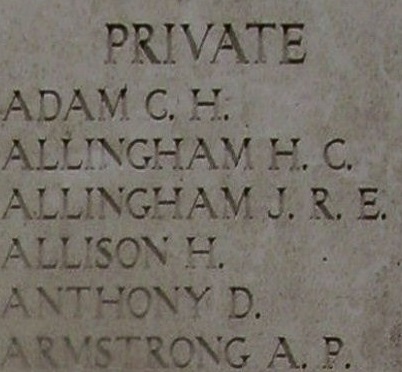

Henry’s name appears on the First World War Book of Remembrance and is carved at the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres.

It’s interesting to note that in the 1916 Census of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, Henry is listed with his family, with a mark to show that he is overseas. A year after Ypres and he is still only listed as missing, not dead in the official war records. That wouldn’t be updated till after the war. Also of interest is where the Allison’s were living in 1916. Some time between 1911 – 1916 they had moved to 590 Pine Street, Winnipeg. The name meant nothing to me, but for those who know their Canadian military history it might ring a bell. In 1925 Pine Street was officially changed to Valour Road, as three young men who lived on it all received a Victoria Cross for acts of bravery in the war. There’s even a Heritage Minute about it.

Corporal Leo Clarke, Sergeant-Major Frederick William Hall, and Lieutenant Robert Shankland all lived within a couple of blocks of Henry Allison. Of them, only Shankland survived the war.

I can understand what drives a young man to enlist and Henry’s choice to fight in the Boer War as a newly married 27-year-old makes some sense to me, the adventure and the belief that you are fighting for Queen and country must have been a powerful lure, but by 1914 his circumstances had changed dramatically. Henry didn’t have to go to war. He was in his forties, a married man with four children, the youngest only seven months old when he left. It’s true that he couldn’t have known what the First World War would be like, but he also wasn’t naive. He would have lost comrades and faced down enemy fire in South Africa, so why sign up to fight once more?

I recoil at the thought of war, so I doubt I will ever understand why he signed up again. Perhaps he thought it his duty, perhaps he believed in the cause, perhaps four children and a wife were not as exciting as his year in South Africa and he was hoping to reclaim his youth. Whatever his reasons, his death left behind a widow and four children who suddenly had to make their own way in the world.

The Allison family story seems to me to be one of broken relationships. Henry left England when he was twenty-five and from what I can tell he never had contact with his family again. His father died in 1913 and doesn’t mention Henry in his will, nor does his older brother, Watson, in his will of 1914. Bill, my great-grandfather, was eight when Henry left for war. As a grown man how much could he really remember of his father? Fifteen years after Henry left, Bill would get a young woman pregnant and marry her quickly before the child was born. Within a few months of my Nana’s birth, though, he would abandon both his wife and child. I have part of a letter he wrote my great-grandmother after the fact, but the only memory my Nana had of him was that he stole a pocket watch from her mother’s family and took off through some orchards when he was caught at it.

My research has fleshed out the Allison family and brought Henry into focus. He was a man who left England and his family behind but fought in two wars for Britain’s interest. He made a life for himself and his family in Winnipeg, but left them to become a soldier once more. For all that I know the facts of his life, Henry, more than any of my other ancestors I’ve written about, still feels like a stranger to me. In the end, all that I’m left with is his name on a wall in Ypres and a picture of a family without a father.